Counterintuitively, people who exercise self control in some way, such as dieting or trying not to look at or think about something, might end up buying things more impulsively instead if given the opportunity.

Vohs & Faber (2007) explain in their study,

Spent Resources: Self-Regulatory Resource Availability Affects Impulse Buying, that opportunities for impulse purchasing have increased with the proliferation of ATMs, shopping on the Internet, and shop-at-home television programs. Depletion of cognitive self-regulatory resources coupled with ever-increasing avenues for impulse buying might just be the answer.

In one experiment, 35 undergraduate participants were made to watch a video of a woman talking on the pretext that they were going to judge her personality later. To suppress one group's attentional resources, irrelevant words were flashed at the bottom of the screen and participants were told to ignore the irrelevant words and focus instead on the woman. Another group was given no such instruction to divert their attention away from the words, and thus served as the control group. After the video, participants were told that they were taking part in a marketing study to determine the prices that students would pay for various products.

It was found that participants who had their attention manipulated assigned significantly higher prices to the products than participants in the control group.

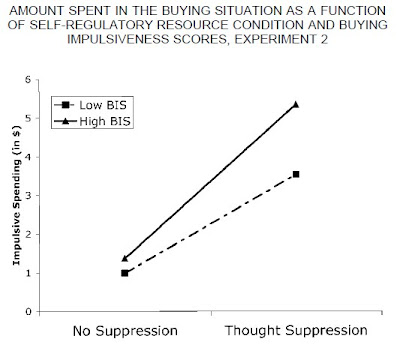

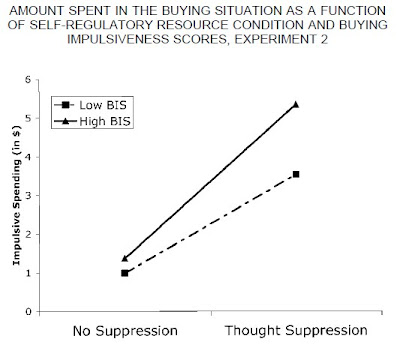

In the second experiment, 73 undergraduates participated by first completing the trait Buying Impulsiveness Scale (BIS), a scale developed by Rook and Fisher (1995) which measures generalized urges to spend impulsively. This was followed by a thought suppression exercise where participants were induced with the thought of a 'white bear', an interesting experimental technique developed by Wegner in 1989 that has been proven to drain considerable cognitive resources. Participants were told to write down their thoughts for the next few minutes. Participants in the Thought Suppression condition were told that they should try and avoid thinking of a white bear and if they did think of a white bear, they should place a check mark on their paper and then resume recording their thoughts. Participants in the No Suppression condition could think of anything they wanted, including white bears.

After this, participants were told that they were going to be involved in a study about introducing new products at the university bookstore. Participants would be given $10 for their participation in the study, after which they could either leave with the money, or they could make a purchase with the items that were available as part of the bookstore's product study.

It was found that spontaneous buying behaviour is once more predicted by mental resource depletion, as students who did not have to suppress their thoughts were more likely to keep the $10 and leave. Additionally, an interaction effect between dispositional buying impulsiveness (as determined by the BIS) and the self-regulatory resource condition was found. As the authors assert, "Among people who are prone to buying impulsively, temporary lapses in self-control ability signal a strong possibility that impulsive, unplanned, and perhaps unwanted spending may occur."

In the last experiment of the study, 40 undergraduate subjects took a variant of the second experiment to determine that the results were not confounded by other cognitive or affective traits, such as the desirability of the items being purchased.

In the last experiment of the study, 40 undergraduate subjects took a variant of the second experiment to determine that the results were not confounded by other cognitive or affective traits, such as the desirability of the items being purchased.

This study extends the research on impulse buying, which has come a long way since the 1980s where people were simply labeled as either impulsive or nonimpulsive purchasers, effectively indicating that there is an interaction between both dispositional and environmental influences that determines impulse-buying. In other words, personality and social factors both play a part. The authors conclude: "Self-regulatory resource availability would be an important element in determining when and why people engage in impulsive spending." Without enough self-regulatory resources, people will be less able to overcome urges and substitute desirable behaviours with undesired ones. Thus, temporary reductions in the capacity to self-regulate leads to stronger impulsive buying tendencies.

From this research, it appears that people in modern contexts do not stand confidently in the ability to control their temptations, as contemporary city-living inundates our senses with a twin barrage of cognitive overload as well as opportunities to spend.

Vohs, K., & Faber, R. (2007). Spent Resources: Self‐Regulatory Resource Availability Affects Impulse Buying Journal of Consumer Research, 33 (4), 537-547 DOI: 10.1086/510228

In the last experiment of the study, 40 undergraduate subjects took a variant of the second experiment to determine that the results were not confounded by other cognitive or affective traits, such as the desirability of the items being purchased.

In the last experiment of the study, 40 undergraduate subjects took a variant of the second experiment to determine that the results were not confounded by other cognitive or affective traits, such as the desirability of the items being purchased.